Navigating the world of filtration can seem complex, but understanding how to choose the right filtration media is fundamental to achieving optimal performance across a vast array of applications. This guide aims to demystify the process, ensuring you can confidently select the most effective solutions for your specific requirements.

Effective filtration is crucial for removing unwanted substances, safeguarding equipment, and ensuring the quality of the final product, whether it’s pure water, clean air, or a refined chemical compound. By thoroughly understanding the contaminants you need to address and the principles behind different filtration technologies, you can make informed decisions that lead to superior results.

Understanding Filtration Needs

Filtration is a critical process across a vast array of industries and applications, serving the fundamental purpose of separating solid particles or impurities from a fluid, which can be a liquid or a gas. This separation is essential for maintaining product quality, protecting equipment, ensuring safety, and optimizing operational efficiency. Whether it’s purifying drinking water, clarifying industrial chemicals, or removing exhaust pollutants, the principles of filtration remain constant: to achieve a desired level of purity by removing unwanted constituents.The effectiveness of any filtration system hinges on a thorough understanding of what needs to be removed.

Different filtration media are designed to target specific types of contaminants, and selecting the wrong media can lead to poor performance, premature clogging, and increased operational costs. Therefore, a detailed analysis of the contaminants present is the cornerstone of successful filtration strategy.

Purpose of Filtration in Various Applications

The primary goal of filtration is to enhance the quality and integrity of fluids by removing undesirable particulate matter. This objective translates into numerous benefits depending on the specific context. In food and beverage production, filtration ensures clarity, removes spoilage organisms, and improves taste and shelf-life. For pharmaceuticals, it is paramount for removing particulate impurities, sterilizing solutions, and ensuring patient safety.

In industrial settings, filtration protects sensitive machinery from abrasive wear, prevents blockages in pipelines and nozzles, and ensures the quality of manufactured goods, such as paints, coatings, and electronic components. Furthermore, environmental protection relies heavily on filtration for treating wastewater, purifying air emissions, and managing industrial effluents to minimize ecological impact.

Common Types of Contaminants Removed by Filtration

Filtration systems are engineered to address a wide spectrum of particulate matter. These contaminants can vary significantly in size, shape, and chemical composition, dictating the choice of filtration media and technology. Understanding these common categories is vital for effective contaminant removal.

- Particulate Matter: This is the most general category and includes any solid particles suspended in a fluid. Examples range from large debris like sand and rust flakes to microscopic particles like silt and fine dust.

- Biological Contaminants: In many applications, filtration is used to remove microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, algae, and fungi. This is particularly critical in water purification, food processing, and pharmaceutical manufacturing.

- Chemical Precipitates: During chemical reactions or due to changes in temperature or pH, insoluble compounds can form and precipitate out of a solution. Filtration is used to separate these precipitates from the desired liquid.

- Colloids: These are very fine particles, typically between 1 nanometer and 1 micrometer in size, that remain suspended in a fluid and do not settle out easily. They can affect clarity and stability in various products.

- Scale and Sediment: In water systems, scale deposits and sediment can accumulate, leading to reduced flow rates and equipment damage. Filtration helps to prevent their formation and accumulation.

- Fines: In processes involving powders or granular materials, fine particles generated during handling or processing can be undesirable and need to be removed.

Importance of Understanding Specific Contaminants

The effectiveness of a filtration system is directly proportional to the accuracy with which the contaminants present in the system are identified and characterized. Generic filtration solutions often prove inadequate, leading to inefficiencies and potential failures. A deep understanding of the specific contaminants allows for the selection of filtration media with the appropriate pore size, chemical compatibility, and mechanical strength to effectively capture the target impurities without compromising the process fluid or the filtration equipment itself.For instance, filtering a viscous oil might require a different approach than filtering potable water.

The size distribution of particles, their concentration, and their tendency to foul or blind the filter media are all crucial factors. Identifying the exact nature of contaminants—whether they are hard and abrasive, soft and compressible, or biological in nature—enables the selection of media that can withstand the operating conditions and efficiently remove the impurities.

Key Performance Indicators for Effective Filtration

To ascertain whether a filtration system is performing optimally, several key performance indicators (KPIs) are monitored. These metrics provide quantifiable data on the system’s efficiency, longevity, and impact on the overall process. Regularly tracking these KPIs allows for timely adjustments, maintenance, and improvements.The following are critical KPIs for evaluating filtration effectiveness:

- Filtration Efficiency (or Purity Level): This measures the percentage of contaminants removed by the filter. It is often expressed as the removal efficiency of particles above a certain size (e.g., 99% removal of particles > 1 micron).

- Pressure Drop: This is the difference in pressure between the inlet and outlet of the filter. An increasing pressure drop typically indicates that the filter is becoming clogged with contaminants and requires cleaning or replacement. A stable and acceptable pressure drop is desirable for consistent flow.

- Flow Rate: This refers to the volume of fluid that passes through the filter per unit of time. A decline in flow rate, often correlated with an increase in pressure drop, signifies filter loading.

- Filter Lifespan (or Service Life): This is the duration for which a filter element effectively performs its function before needing replacement or regeneration. It is influenced by contaminant load, operating conditions, and the filter’s capacity.

- Media Compatibility: This KPI assesses how well the filtration media interacts with the process fluid and contaminants. It ensures that the media does not degrade, leach chemicals, or react unfavorably with the fluid being filtered.

- Cost of Filtration: This encompasses the total cost associated with the filtration process, including the initial purchase of filter media, energy consumption, labor for maintenance and replacement, and disposal costs.

“The true measure of filtration effectiveness lies not just in what it removes, but in how efficiently, economically, and reliably it achieves the desired purity.”

Types of Filtration Media

Understanding the diverse array of filtration media available is crucial for selecting the most effective solution for your specific needs. Each type operates on distinct principles and excels in different applications, from removing physical particles to altering chemical compositions. This section provides a comprehensive overview of common filtration media categories, their operational mechanisms, advantages, and typical uses.This exploration will delve into four primary categories of filtration media: mechanical filters, adsorption media, ion exchange resins, and biological filters.

By understanding the unique characteristics of each, you can make informed decisions to achieve optimal filtration performance.

Mechanical Filters

Mechanical filters are designed to physically trap and remove solid particles from a fluid. Their operation relies on the size of the pores or the intricate pathways within the filter medium, preventing particles larger than a specific micron rating from passing through. This method is fundamental in removing suspended solids, sediment, and other particulate matter.The principle of operation is straightforward: as the fluid flows through the filter medium, solid contaminants are retained on the surface or within the matrix of the material.

The effectiveness of mechanical filtration is primarily determined by the pore size and the depth of the filter medium.Typical applications include pre-filtration for other filtration systems, removal of rust and scale from water lines, and clarification of liquids in food and beverage industries. The primary advantage of mechanical filters is their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to remove a wide range of particulate sizes.Examples of mechanical filter materials include:

- Sediment Filters: Often made from pleated materials like polyester or polypropylene, or spun fibers, these are designed to capture larger particles.

- Cartridge Filters: These are typically cylindrical and can be made from various materials, including wound string, pleated fabric, or depth media, offering a range of micron ratings.

- Screen Filters: Constructed from woven mesh, these are effective for removing larger debris and are often used as a first stage of filtration.

Adsorption Media

Adsorption media work by attracting and holding contaminants on their surface through physical or chemical forces. Unlike mechanical filtration, which physically blocks particles, adsorption targets dissolved substances, chemicals, and organic compounds. This process is highly effective for removing impurities that cannot be physically strained out.The principle of operation involves a high surface area and specific chemical properties of the adsorbent material that create an affinity for target contaminants.

Contaminants adhere to the surface of the media, effectively removing them from the fluid stream.Common applications include the removal of chlorine, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), taste and odor compounds from water, and purification of gases. The key advantages are their ability to remove dissolved impurities, improve aesthetic qualities of water, and their often regenerable nature, extending their lifespan.Examples of adsorption media include:

- Activated Carbon: This is one of the most widely used adsorption media due to its exceptionally high surface area and porous structure. It effectively removes chlorine, organic contaminants, and improves taste and odor.

- Zeolites: These are naturally occurring or synthetic porous aluminosilicate minerals. They can adsorb certain polar molecules and are also used for ion exchange.

- Activated Alumina: Primarily used for removing fluoride, arsenic, and selenium from water.

A key characteristic of activated carbon is its vast internal surface area, which can be as high as 1000-1500 square meters per gram, providing ample sites for contaminant adsorption.

Ion Exchange Resins

Ion exchange resins are specialized polymers that selectively remove dissolved ionic contaminants from water and other solutions. They function by exchanging ions in the fluid with ions attached to the resin beads. This process is crucial for water softening, demineralization, and the removal of specific toxic ions.The principle of operation involves charged functional groups on the resin beads. Cations (positively charged ions) are exchanged for other cations, and anions (negatively charged ions) are exchanged for other anions.

The resin is initially “charged” with a desired ion (e.g., sodium ions for water softening), and as contaminated water passes through, the target ions in the water bind to the resin, releasing the original ions.Typical applications include water softening to remove calcium and magnesium, deionization for producing high-purity water in laboratories and industries, and the removal of heavy metals like lead and copper.

The main advantages are their high selectivity for specific ions, their ability to achieve very low contaminant concentrations, and their regenerability.Examples of ion exchange resins include:

- Cation Exchange Resins: Used to remove positively charged ions like calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium.

- Anion Exchange Resins: Used to remove negatively charged ions like sulfate, nitrate, chloride, and silica.

- Mixed-Bed Resins: A combination of cation and anion exchange resins used to produce highly purified water by removing virtually all dissolved ionic impurities.

For example, in water softening, a cation exchange resin typically in the sodium form is used. When hard water containing calcium (Ca²⁺) and magnesium (Mg²⁺) ions flows through the resin, these ions are captured by the resin, and sodium ions (Na⁺) are released into the water. The reaction can be represented as:

2R-Na + Ca²⁺ → R₂-Ca + 2Na⁺

where R represents the resin matrix.

Biological Filters

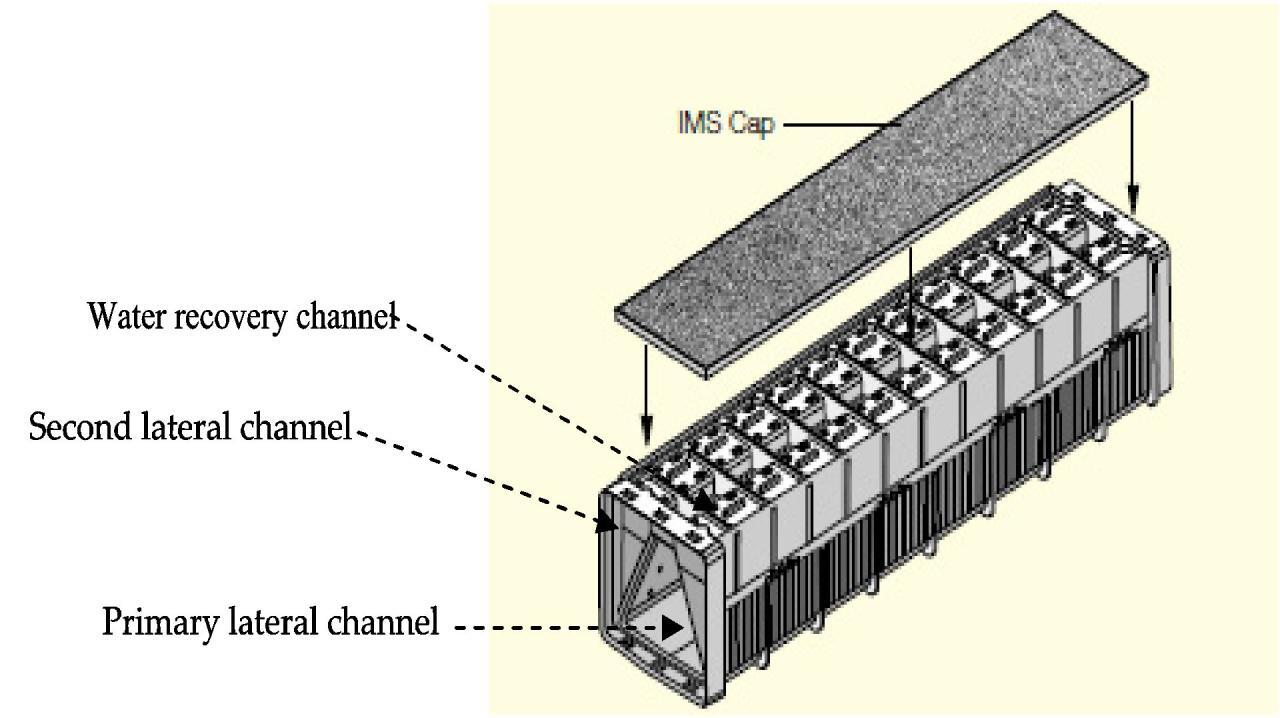

Biological filters utilize beneficial microorganisms to break down organic pollutants and contaminants in water. This method is particularly effective for wastewater treatment and aquariums, where organic waste can accumulate and become harmful.The principle of operation involves creating an environment where a biofilm, a layer of microorganisms, can thrive on a media surface. As wastewater passes over the biofilm, the microorganisms consume and metabolize organic compounds, converting them into less harmful substances such as carbon dioxide, water, and nitrates.Typical applications include municipal wastewater treatment, aquaculture, and pond filtration.

The advantages of biological filtration are its ability to remove dissolved organic matter that other methods cannot, its cost-effectiveness for large-scale treatment, and its environmentally friendly nature.Examples of biological filter media include:

- Gravel and Sand: Traditional media providing a large surface area for biofilm growth.

- Plastic Bio-balls and Media: Lightweight, high-surface-area plastic structures designed to maximize contact between water and microorganisms.

- Sponge and Foam: Porous materials that support robust biofilm development.

The effectiveness of a biological filter is directly related to the health and activity of the microbial community within the biofilm, which in turn depends on factors like oxygen availability, temperature, and nutrient levels.

Factors Influencing Media Selection

Selecting the appropriate filtration media is a crucial step in ensuring the efficiency and effectiveness of any filtration system. This process involves a careful evaluation of several interconnected factors that dictate how well a particular media will perform in a given application. Understanding these influences allows for informed decisions that optimize performance, longevity, and cost-effectiveness.The optimal filtration media is not a one-size-fits-all solution; rather, it is a carefully chosen component tailored to the unique demands of the fluid being processed and the desired outcome.

A systematic approach to evaluating these influencing factors is essential for achieving the best possible results and avoiding potential operational issues.

Flow Rate Requirements

The volume of fluid that needs to be processed over a specific period is a primary determinant in selecting filtration media. A higher flow rate typically requires media with larger pore sizes or a greater surface area to avoid excessive pressure drop and premature clogging. Conversely, lower flow rates may allow for finer media capable of capturing smaller particles.

Consider the following aspects when evaluating flow rate requirements:

- Nominal Flow Rate: The expected average flow rate during normal operation.

- Peak Flow Rate: The maximum flow rate the system might experience, which can occur during startup, shutdown, or process upsets.

- Pressure Drop Tolerance: The acceptable increase in pressure across the filter at the required flow rate. High flow rates through fine media can lead to significant pressure drops, impacting pump efficiency and potentially damaging the system.

Temperature and Pressure of the System

The operating temperature and pressure of the fluid significantly influence the material properties and structural integrity of the filtration media. Certain media can degrade, lose their effectiveness, or even fail under extreme conditions. Therefore, selecting media that can withstand the system’s thermal and pressure stresses is paramount for safety and performance.

Key considerations for temperature and pressure include:

- Maximum Operating Temperature: The highest temperature the fluid will reach. This impacts the thermal stability of the media material. For instance, some polymers may soften or degrade at elevated temperatures, while certain ceramics or metals are suitable for high-temperature applications.

- Minimum Operating Temperature: Low temperatures can cause some media to become brittle or freeze, leading to damage.

- Maximum Operating Pressure: The highest pressure the filter housing and media will be subjected to. The media must possess sufficient structural integrity to resist collapse or deformation under these conditions.

- Pressure Fluctuations: Systems with frequent or significant pressure swings require media that can tolerate these dynamic loads without delamination or rupture.

Chemical Compatibility of the Media with the Fluid

The interaction between the filtration media and the fluid being filtered is critical. Incompatibility can lead to degradation of the media, contamination of the fluid, or a loss of filtration efficiency. It is essential to ensure that the media material is chemically inert to the fluid and any other chemicals present in the system.

When assessing chemical compatibility, consider:

- Corrosivity: The fluid’s potential to corrode or dissolve the media material. Acids, bases, and strong solvents are common culprits.

- Reactivity: Whether the media material can react with components in the fluid, potentially forming unwanted byproducts or altering the fluid’s properties.

- Leaching: The possibility of the media material leaching substances into the fluid, which can be problematic in sensitive applications like pharmaceuticals or food and beverage processing.

- Solvent Effects: If the fluid contains solvents, ensure the media is resistant to swelling, shrinking, or dissolving in them.

The principle of “like dissolves like” is a useful starting point for predicting chemical compatibility, but empirical testing or consulting manufacturer compatibility charts is always recommended for critical applications.

Desired Level of Purification or Contaminant Removal

The primary goal of filtration dictates the required fineness of the media. Whether the objective is to remove large debris, fine particulates, or even dissolved contaminants, the choice of media must align with the target particle size and the required purity of the filtered fluid.

Different levels of purification require distinct approaches:

- Bulk Filtration: For removing large particles (e.g., rust, scale), coarser media like mesh or woven fabrics are often sufficient.

- Fine Filtration: To remove smaller suspended solids, finer pore media such as depth filters or pleated cartridges are employed. The pore size rating (e.g., in microns) becomes a critical specification.

- Absolute vs. Nominal Filtration: Absolute filters are rated to remove a specific percentage of particles of a given size (e.g., 99.9% of particles larger than 1 micron), while nominal filters provide a less precise indication of particle removal.

- Specialized Filtration: For removing dissolved substances, activated carbon or ion exchange resins might be necessary, which operate on principles beyond simple mechanical sieving.

Cost Considerations (Initial and Ongoing)

The economic aspect of filtration media selection involves balancing initial purchase costs with long-term operational expenses. While a cheaper media might seem attractive upfront, it could lead to higher replacement frequency, increased labor costs, and potential production downtime, ultimately proving more expensive.

A comprehensive cost analysis should include:

- Initial Purchase Price: The upfront cost of the filtration media itself.

- Installation Costs: Labor and materials associated with replacing the media.

- Replacement Frequency: How often the media needs to be changed, which is influenced by its lifespan and the contaminant load.

- Disposal Costs: The cost associated with safely disposing of used filtration media, especially if it is considered hazardous.

- Energy Costs: Higher pressure drops associated with some media can increase pump energy consumption.

- Product Loss: In some cases, inefficient filtration can lead to product loss or rework, adding to the overall cost.

Lifespan and Replacement Frequency

The expected operational life of the filtration media directly impacts maintenance schedules and overall system uptime. Factors such as the contaminant load in the fluid, operating conditions (temperature, pressure), and the media’s inherent durability all contribute to its lifespan. A media with a longer lifespan may justify a higher initial cost.

Estimating lifespan and replacement frequency involves:

- Contaminant Loading: A higher concentration of contaminants will reduce the media’s effective lifespan.

- Operating Conditions: Extreme temperatures, pressures, or chemical environments can accelerate media degradation.

- Media Type and Construction: Different materials and designs offer varying levels of durability and resistance to fouling.

- Monitoring and Maintenance Schedules: Regular monitoring of pressure drop and visual inspection can help predict when replacement is necessary, preventing catastrophic failure.

Decision-Making Framework and Prioritization

To effectively choose the right filtration media, it is beneficial to employ a structured decision-making framework that systematically evaluates each factor. Prioritizing these factors based on the criticality of the application ensures that the most important criteria are addressed first, leading to a robust and reliable filtration solution.

A potential framework involves the following steps:

- Define Application Requirements: Clearly state the fluid type, flow rate, temperature, pressure, and the exact level of purification needed.

- Identify Potential Media Candidates: Based on the initial requirements, research and shortlist media types that could potentially meet the needs.

- Evaluate Against Critical Factors: Systematically assess each candidate media against the factors discussed: flow rate capacity, temperature/pressure limits, chemical compatibility, contaminant removal efficiency, cost, and expected lifespan.

- Perform Risk Assessment: For each candidate, consider the potential consequences of media failure or suboptimal performance.

- Prioritize Factors: Determine which factors are non-negotiable for the specific application. For example, in pharmaceutical manufacturing, chemical compatibility and purity are paramount, potentially overriding initial cost. In a less critical industrial process, cost might be a more significant driver, provided performance targets are met.

- Select and Test: Choose the media that best balances all requirements and, if possible, conduct pilot testing to validate performance under actual operating conditions.

Prioritizing Factors Based on Application Criticality

The criticality of an application dictates the hierarchy of importance for the selection factors. In highly sensitive or safety-critical systems, certain factors will inherently carry more weight than others.

Examples of prioritization based on criticality include:

- Pharmaceutical and Food & Beverage: Purity and chemical compatibility are paramount. The media must not leach any substances into the product, and its inertness is non-negotiable. Cost is secondary to safety and regulatory compliance.

- High-Temperature Industrial Processes: Temperature and pressure resistance are the primary drivers. Media must withstand extreme conditions without degradation, even if it means a higher initial investment.

- General Industrial Water Filtration: Flow rate, cost, and lifespan often take precedence. The goal is to achieve adequate filtration at a reasonable operating expense.

- Aerospace and Automotive: Reliability and performance under extreme conditions are critical. Media failure can have severe safety implications, making robustness and precise contaminant removal key considerations, often justifying premium materials.

Matching Media to Specific Applications

Selecting the correct filtration media is paramount to achieving the desired purity and performance for a wide array of applications. This section delves into how to align filtration media with specific scenarios, ensuring optimal results and addressing common challenges. By understanding the interplay between contaminants, application requirements, and media properties, users can make informed decisions that lead to efficient and effective filtration systems.The choice of filtration media is not a one-size-fits-all proposition.

Each application presents a unique set of challenges, from the types of impurities present to the required level of clarity or purity. Therefore, a targeted approach is necessary to identify the most suitable media for each specific use case.

Water Purification

Water purification encompasses a broad spectrum of needs, from ensuring safe drinking water to processing water for industrial applications. The contaminants targeted and the acceptable levels of purity vary significantly between these scenarios.For drinking water, the primary concerns are the removal of sediment, chlorine, dissolved organic compounds, heavy metals, and potentially microorganisms. Activated carbon is highly effective at adsorbing chlorine, improving taste and odor, and removing certain organic chemicals.

Ceramic filters, with their fine pore structure, are excellent for removing sediment and bacteria. For the most stringent purification, reverse osmosis membranes can remove a vast range of dissolved solids, including salts and heavy metals, though they also remove beneficial minerals.Industrial water purification often requires more robust solutions depending on the industry. For example, in power generation, demineralization might be crucial, utilizing ion-exchange resins.

In electronics manufacturing, ultra-pure water is essential, often achieved through a multi-stage process involving RO, ion exchange, and UV sterilization.

Air Filtration

Air filtration plays a vital role in both comfort and health, as well as in protecting sensitive equipment and processes in industrial settings. The goal is to remove particulate matter, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), odors, and sometimes biological contaminants.In residential and commercial HVAC systems, the focus is typically on removing dust, pollen, and other airborne allergens to improve indoor air quality.

Pleated filters made from synthetic fibers are common, with MERV (Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value) ratings indicating their effectiveness. For higher efficiency, HEPA (High-Efficiency Particulate Air) filters can remove 99.97% of particles 0.3 microns in size. Activated carbon panels are frequently incorporated into HVAC systems to adsorb odors and VOCs.Industrial air filtration often deals with more challenging contaminants. Manufacturing processes can release fine dust, chemical fumes, and VOCs.

HEPA filters are essential for cleanrooms and sensitive manufacturing environments. Activated carbon is indispensable for removing chemical vapors and odors in industries such as chemical processing, printing, and food production. Specialized filters are also available for capturing specific hazardous materials or fine mists.

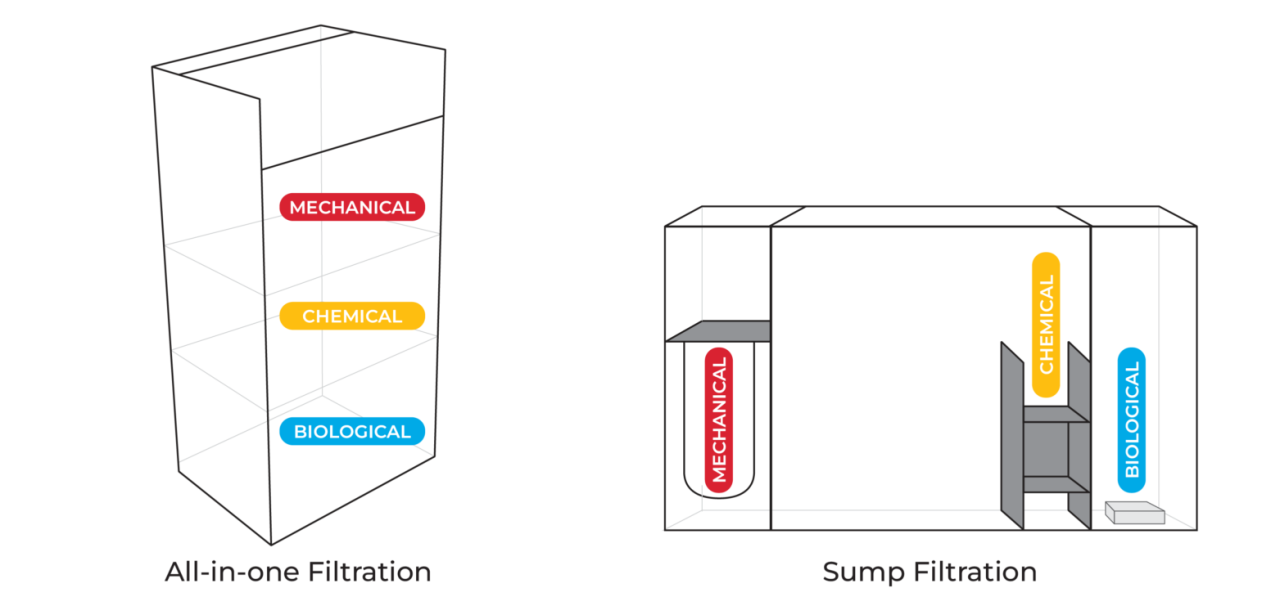

Aquarium Filtration

Maintaining a healthy aquatic environment relies heavily on effective filtration to remove waste products and maintain water clarity. The key contaminants in aquariums are ammonia (from fish waste), nitrites, nitrates, and suspended particulate matter.Mechanical filtration, often using sponge filters or filter floss, is crucial for removing visible debris and larger particles. Biological filtration is perhaps the most critical aspect, where beneficial bacteria colonize porous media (bio-media) to convert toxic ammonia into less harmful nitrates.

Materials like ceramic rings, bio-balls, and specialized porous stones provide ample surface area for these bacteria. Activated carbon is often used as a polishing filter to remove dissolved organic compounds, which can cause discoloration and odor, and to absorb medications after treatment.

Chemical Processing

In chemical processing, filtration is used for a variety of purposes, including product purification, catalyst recovery, solvent clarification, and protecting downstream equipment. The choice of media is heavily dependent on the specific chemicals involved, operating temperatures, pressures, and the desired level of purity.Commonly used media include various types of filter cloths and bags made from materials like polypropylene, polyester, or PTFE, chosen for their chemical resistance.

Cartridge filters with depth or pleated media are also employed. For highly demanding applications requiring the removal of very fine particles or specific dissolved impurities, advanced media such as membrane filters or specialized adsorbent materials might be necessary. It is critical to ensure the filtration media does not react with or degrade in the presence of the chemicals being processed.

Food and Beverage Production

Filtration in the food and beverage industry is essential for ensuring product safety, quality, and shelf life. Applications range from clarifying juices and wines to sterilizing dairy products and filtering beer.For particulate removal, depth filters and pleated filters made from food-grade materials are widely used. Activated carbon is employed for decolorization and the removal of off-flavors and odors in products like sugar syrups, edible oils, and beverages.

Membrane filtration, including microfiltration, ultrafiltration, and nanofiltration, plays a significant role in clarifying liquids, concentrating products, and achieving microbial stabilization without heat. Sterilizing filters, often with pore sizes of 0.2 microns or less, are critical for removing bacteria and other microorganisms from heat-sensitive products.

| Application | Common Contaminants | Recommended Media Types | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking Water | Sediment, chlorine, heavy metals, organic compounds, bacteria | Activated Carbon, Ceramic Filters, Reverse Osmosis Membranes, Ultrafiltration Membranes | Taste, odor, health safety, mineral content, flow rate |

| Industrial Water (e.g., Boiler Feed) | Dissolved solids, suspended solids, silica | Ion Exchange Resins, Reverse Osmosis Membranes, Sediment Filters | Demineralization, conductivity, process efficiency |

| Industrial Air (e.g., Manufacturing) | Particulates (dust, smoke), VOCs, odors, fumes | HEPA Filters, Activated Carbon Panels, Pleated Filters (high MERV) | Efficiency, air quality standards, particle size removal, chemical adsorption capacity |

| Aquarium | Ammonia, nitrites, nitrates, particulates, dissolved organics | Sponge Filters, Bio-media (ceramic rings, bio-balls), Activated Carbon, Filter Floss | Water clarity, fish health, biological balance, nutrient export |

| Chemical Processing (e.g., Solvent Clarification) | Particulates, catalyst fines, insoluble impurities | Depth Filters, Pleated Cartridge Filters (various materials like PP, PTFE), Filter Cloths | Chemical compatibility, temperature/pressure resistance, particle retention efficiency, cost |

| Food and Beverage Production (e.g., Juice Clarification) | Yeast, bacteria, pulp, haze, color compounds | Depth Filters, Pleated Filters (food-grade), Membrane Filters (MF, UF), Activated Carbon | Food safety compliance, product integrity, clarity, shelf life, taste/odor profiles |

Troubleshooting Common Filtration Issues Related to Media Choice

When filtration systems aren’t performing as expected, the filtration media is often a primary suspect. Understanding common issues and their relation to media selection can expedite troubleshooting.One prevalent problem is reduced flow rate. This can occur if the media’s pore size is too small for the contaminant load, leading to rapid clogging. For instance, using a very fine-pore ceramic filter for heavily sediment-laden water will quickly become blocked.

The solution often involves selecting a media with a larger pore size or implementing a pre-filtration stage.Another issue is incomplete contaminant removal. If drinking water still has an unpleasant taste or odor, the activated carbon may be exhausted or of insufficient capacity. Similarly, if an industrial process is not achieving the desired purity, the chosen media might not be effective against specific dissolved contaminants or may have a limited lifespan.

This points to a need for a more robust media type or a different filtration technology altogether.Premature media degradation or fouling can also occur. This is particularly relevant in chemical processing where incompatible media can break down, contaminating the product. Ensuring the media’s chemical resistance and operating temperature limits are met is crucial. In biological filtration, a lack of adequate surface area or poor water flow can hinder the development of beneficial bacteria, leading to ammonia spikes in aquariums.

The efficacy of a filtration system is directly proportional to the suitability of its media for the specific contaminants and operational conditions.

If a filter fails to capture expected particles, it could indicate a breach in the filter integrity or that the media’s rated efficiency is insufficient for the target particle size. For HEPA filters, a loss of seal or damage can compromise performance. For any application, regular monitoring of pressure drop across the filter is a key indicator of clogging and potential media issues.

If the pressure drop increases significantly, it suggests the media is becoming blocked. Conversely, a consistently low pressure drop might indicate that the media is not effectively capturing contaminants.

Maintenance and Replacement Strategies

Proper maintenance and timely replacement of filtration media are crucial for ensuring the consistent performance and longevity of any filtration system. Neglecting these aspects can lead to reduced efficiency, increased operational costs, potential damage to equipment, and compromised quality of the filtered substance. This section will delve into the essential strategies for maintaining filtration media and determining when it’s time for a change.

Assessing Filtration Media Performance and Remaining Life

Regularly evaluating the condition and effectiveness of filtration media is key to proactive maintenance. Several methods can be employed to gauge performance and estimate the remaining operational life, allowing for informed decisions regarding cleaning or replacement.Several indicators can signal a need for attention:

- Pressure Drop: An increasing pressure drop across the filter signifies that the media is becoming clogged with contaminants, restricting flow. This is a primary metric for assessing media saturation.

- Flow Rate Reduction: A noticeable decrease in the system’s flow rate, even with consistent pressure, indicates that the media’s capacity to allow passage is diminishing.

- Visual Inspection: For some media types, a visual check can reveal significant fouling, discoloration, or physical degradation. This is often done during routine system checks.

- Water Quality Analysis (for water filtration): Monitoring the quality of the filtered output, such as turbidity, pH, or specific contaminant levels, can indicate if the media is no longer effectively removing target substances.

- Contaminant Loading: In systems where contaminant levels are monitored, a sharp increase in the amount of captured material can suggest the media is nearing its saturation point.

Determining Optimal Replacement Schedules

Establishing an optimal replacement schedule for filtration media involves balancing performance requirements, cost-effectiveness, and potential risks. While some media types have manufacturer-recommended replacement intervals, actual service life can vary significantly based on operating conditions and the nature of the contaminants.Consider the following when setting schedules:

- Manufacturer Recommendations: Always consult the manufacturer’s guidelines for initial replacement intervals, as these are based on specific media properties and intended applications.

- Operating Conditions: Systems operating in highly contaminated environments or under heavy load will require more frequent replacements than those with lighter duty cycles.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Evaluate the cost of premature replacement against the cost of potential system downtime, reduced product quality, or damage caused by a saturated filter.

- Performance Monitoring Data: Use the data gathered from performance assessments (pressure drop, flow rate, etc.) to refine replacement schedules. If a filter consistently reaches a critical pressure drop before the recommended interval, adjust the schedule accordingly.

- Media Type and Application: Different media have vastly different lifespans. For instance, a disposable cartridge filter for a home air purifier will have a much shorter replacement cycle than a deep-bed sand filter in an industrial water treatment plant.

Environmental Impact and Disposal Options

The disposal of used filtration media is an important consideration, as it can contain captured hazardous or non-hazardous contaminants. Responsible disposal practices are essential to minimize environmental impact.Common disposal considerations include:

- Hazardous Waste Classification: Determine if the used media is classified as hazardous waste based on the contaminants it has captured. This will dictate specific handling and disposal regulations.

- Landfilling: Non-hazardous spent media may be disposed of in approved landfills. Ensure compliance with local regulations regarding landfill acceptance criteria.

- Incineration: For certain types of organic contaminants, incineration might be a suitable disposal method, often at specialized facilities.

- Recycling and Reclamation: Investigate options for recycling or reclaiming the filtration media, particularly for reusable media like activated carbon or certain ceramic filters. Some manufacturers offer take-back programs.

- Wastewater Treatment: If the media is removed as part of a wastewater treatment process, the disposal of the captured solids will follow established wastewater sludge management protocols.

Basic Maintenance Checklist for Common Filtration Systems

A structured maintenance checklist helps ensure that all critical aspects of filtration system upkeep are addressed systematically. This checklist is a general guide and should be adapted to specific system types and operational requirements. Daily/Weekly Checks:

- Visual inspection of the filter housing for leaks or damage.

- Check pressure gauges for significant deviations from normal operating pressure.

- Verify flow rate against expected performance.

- Listen for unusual noises from the system that might indicate issues.

Monthly Checks:

- Record pressure drop and flow rate data to track trends.

- Perform a more thorough visual inspection of accessible media elements.

- Check seals and gaskets for wear or degradation.

- If applicable, sample filtered output for basic quality checks.

Quarterly/Semi-Annual Checks:

- Clean or replace disposable filter cartridges as per schedule or performance indicators.

- For reusable media, perform cleaning procedures (e.g., backwashing, soaking).

- Inspect for signs of media degradation or channeling.

- Review maintenance logs and adjust schedules based on observed performance.

- Assess inventory of spare parts and consumables.

Annual Checks:

- Full system flush and deep cleaning.

- Replace any media that has reached its recommended service life, even if performance indicators are still within acceptable limits.

- Inspect the entire filtration unit for structural integrity.

- Review and update maintenance procedures and safety protocols.

- Dispose of any spent media according to environmental regulations.

Conclusion

In essence, selecting the appropriate filtration media is a strategic decision that hinges on a deep understanding of your system’s needs, the characteristics of available media, and the critical factors influencing performance and cost. By following a structured approach, from identifying contaminants to considering operational parameters and maintenance, you can confidently implement filtration solutions that are both effective and economical, ensuring the long-term health and efficiency of your systems.